Students in our program should critically evaluate research and draw in developed theoretical paradigms to advance equitable educational approaches.

Going through the interview process recently, one of the questions asked is always some form of “how do you use data to drive instruction?” so it is no secret that schools are using data to inform instruction and want teachers that can do that on the classroom scale. Evaluating research is taking instruction to the next level, where teachers are not only evaluating student data at their campus, but are looking at best practice theories, supported by research and enacting them in their careers to further learning for every individual student.

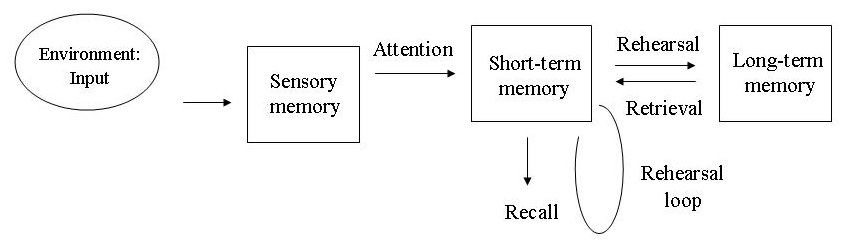

Before looking at best practices and theories, it is important to look at how the brain takes in, processes, and stores information, or the process of learning. While “there is no general agreement about the definition of learning” there is a widely supported model of memory and acquisition (De Houwer, 2013). This method is commonly known as Atkinson and Shiffrin’s modal model of memory, which involves 3 main components. Short term memory, long term memory, and sensory memory (Goldstein, 2014). This model states that a person takes in information to their sensory memory, which the brain immediately decides if it is important or not, and if so, it moves the information to short term memory, with 5-9 other facts for about 20 seconds. Through repetition, the fact is strengthened and if deemed important enough to remember, it is moved to long term memory. For usage later, a fact is recalled from long term memory and repeated once again, which further strengthens the information. Over time with constant repetition, the piece of information can be called with no effort, making it intrinsic.

What this means for the classroom, is that information is best learned when repeated frequently, especially when a new concept is introduced longer than the 20 seconds it is stored in short term memory. If repeated, the concept will transfer to long term memory of a student’s brain and through increased repetition, will become solidified and easier for students to recall, therefore meeting the criteria of a concept learned.

This constant rehearsal of information is also what makes using technology in the classroom a huge benefit to teachers. Effective technology applications are permanent, accessible, immediate, interactive, authentic, and sustainable (Ogata & Yano, 2004, p.1; Ng & Nicholas, 2013, p. 696). In short, this means that technology has to store user data, be user friendly to the general population, give real information in a very short time frame, and be a program that can be used over time, or more than once. If an application does not meet these 6 goals, then it will not be successful nor will it be beneficial to teachers or the classroom.

Programs such as Prodigy or IXL are repetitive, with goal specific skills that rely on short term repetition to strengthen the long-term knowledge of that skill, causing students to recall the information easily and retain it (IXL, 2021; Prodigy, 2021). These programs respond to each answer with immediate feedback, and either have a wealth of content for students to work through or a long-term recall goal for students to reach, making the programs sustainable. They are also in multiple languages, and work through desktop or tablet applications, making them accessible. They also have individual accounts for each student, tracking their progress in skills, which is why these programs are utilized in classrooms across the United States. These programs as so successful in classrooms because they follow the outline and qualifications of effective programs as defined by Ogata and Yano (2004) and Ng and Nicholas (2013).

The presence of technology alone, can positively impact the knowledge and skills of students in a classroom even if they are not allowed to use it. It has been shown that just by the teacher having a cell phone, without any other technology in the classroom, that student attendance improves and is directly correlated to the number of chat messages a teacher sends to colleges pertaining to their classes (Nedungadi et al., 2018, p. 123). Given to teachers in rural India, these phones were used to trade lesson plans between inexperienced teachers, and with each interaction between colleagues, the better their lesson plans were, and the greater attendance their classes had, which also raised student scores on common assessments since they were present to receive the information taught. This further proves Atkinson and Shiffrin’s modal model of memory, since the more times a child hears a concept, the stronger it becomes in their long-term memory (Goldstein, 2014). The frequency of repetition is increased with each day a student is in the classroom, and the desire to be in the classroom was increased with the more lessons the teachers traded because it made school more entertaining for the students (Nedungadi et al., 2018).

Understanding how one learns and how they connect with the curriculum is also important. Understanding that learners use their prior knowledge and beliefs to make sense of the learning they experience in school is an important step towards equitable education because this acquisition system relies on the feedback loop from short to long term memory to create stronger recalls of information (Lucas, 2007). In short, the more connections educators can make to a student’s circumstances, family, or life outside of school, the more likely they are to remember what they learned. Morrison (2017) utilized the funds of knowledge from parents to create those connections when talking with her first-grade class about the seasons. Since many student’s parents worked in agriculture, they started to focus on Strawberries, and Morrison took advantage of the student’s background knowledge to have them ask and interview their parents for information, which they shared and compared with the class. In creating curriculum that extends the learning outside of the classroom, students are retaining the information longer and making more real-world connections to strengthen their memory. While using the information a student learns from their family, educators are also ensuring the TEKS reflect the needs of the student, rather than the needs of the structural benefits created by a faulty system (Baldwin, 1963).